Savanah Leaf is a name that you will know about soon, beginning with her unusual and stunning background as a director: she’s a former Olympian, a former path that makes sense when you see what she brings behind the camera. A visual artist with music video history, Leaf makes her feature debut with the soulful and impressive “Earth Mama,” which has already been acquired by A24 and made its premiere in the festival’s non-competition Premieres section. “Earth Mama” has a few poetic flourishes that are overly familiar with indie movies of this type (and from this festival), but it is a wildly confident debut that displays Leaf’s great control of performances and filmmaking.

Based on a short film she made with Taylor Russell, “Earth Mama” follows a mother named Gia (Tia Nomore in an amazing debut performance) who is being pulled in many different directions. She’s pregnant and struggling to make ends meet at her job, working at a photo portrait studio, and also trying to gain more visiting time with her two children who have been taken away from her by the state. One option that weighs on her mind is the possibility of open adoption, as advocated by her caseworker, Miss Carmen (Erika Alexander). But that haunts Gia, too.

“Earth Mama” is confident enough to let the choice of open adoption remain the largest stakes, creating a fitfully tense experience. In a handful of scenes that Leaf’s direction plays out for immersive, long takes, Nomore’s work is restrained while everything wrenches inside her. The various pieces of her life make for gripping visual sequences that make the film’s heart even bigger. We get to know the lives of other people around her—people who grew up without parents or mothers who speak in court-mandated group therapy sessions. “Earth Mama” wrestles with how empathy can be both universal and specific simultaneously; “It’s my journey, it’s not no one else’s journey,” one of the mothers says at the beginning of Leaf’s film, looking right at the camera.

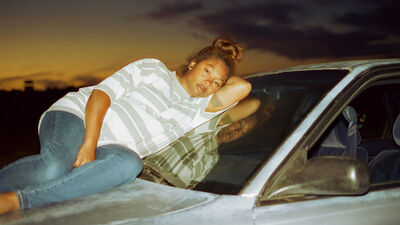

With such adventurous storytelling, certain tropes within stand out—the salvation of water is one of the most common devices from a Sundance-anointed drama; the same with its fluttering, dreamy score. But “Earth Mama” tackles this story with bold cinematography, particularly in how Leaf often shoots her characters in profile. It’s how we watch them as they drive at night, talk, or gaze out of windows. It also makes for a few uneasy and long shots, like one in which we travel alongside Gia as she walks through a screeching nighttime car rally about to confront a friend who represents a shame Gia does not want to face. “Earth Mama” has us observe Gia’s stresses with the up-close rawness of a Dardennes brothers movie, but makes clear we’ll be talking about what makes “A Savanah Leaf Film” soon enough.

Call it an anti-Sundance Sundance movie: Babak Jalali’s “Fremont,” which premiered in the NEXT section, has the knowing constructs of what could make for a quirky comedy. In a nutshell, it’s about a fortune cookie factory worker who goes to see a therapist so that she can get sleeping pills. And when the position opens up for someone to write the fortunes, it becomes an opportunity for her to make an anonymous connection.

Some slightly funny things are swirling around the film’s reserved hero, Donya, but she is not laughing. The premise of “Fremont” instead unfolds as if the jokes have all been taken out, while it tells a sincere character study of an Afghan immigrant wrestling with identity and isolation. The movie is shot mostly with a static camera, creating a deep emotional stasis in this gorgeous black-and-white world crafted by cinematographer Laura Valladao.

Anaita Wali Zada gives a fascinating performance and is in every scene. Her tempered facial expression is often the same throughout. Written by Jalali and Carolina Cavalli, “Fremont” follows her as she mostly listens to people—a quirky co-worker, a restaurant owner who watches soap operas, and her neighbors from Afghanistan. It makes for a striking experience as fundamental but illustrative as the Kuleshov effect, in which we read whatever her face is saying by the conversation it’s intercut with. Sometimes Zada’s work nudges to disappointment, fear, or irritation. Her performance is a work of the quietest passion, a perfect complement to Jalali’s film.

There is scattered talk about Donya’s life story and how people do and don’t change; scenes that dance around what’s on her mind. When she gets the number of a therapist (Gregg Turkington’s Dr. Anthony), he coaxes out her story over a few sessions. She was a translator in Afghanistan for the Americans and has immense guilt about leaving her family behind. We don’t see any of this and don’t need to. We just get the aftermath, these therapy sessions. Much of the film takes place between the two. At one point, Dr. Anthony goes on a tangent about the symbolism in White Fang, and it’s about the largest bid this movie makes to be funny.

I admit to not being able to initially get into the movie’s droll groove—for every detail that makes you think “Fremont” is finally opening up, it resists. Even the appearance of Jeremy Allen White as a new odd duck in Donya’s life, much later in the film, challenges what’s expected in terms of tone or plot. But “Fremont” is also one of the films I’ve thought about most since seeing it at Sundance. It conjures a hum-drum hypnosis with its pacing, the way it goes from one slightly revealing interaction to another; even Turkington’s lip-smacking during the therapy sessions becomes metronomic, albeit at the slowest BPM possible. “Fremont” finds depth in the seemingly bland, and can make you feel so much for its characters because it has very few open feelings itself.