Even if he had essayed the role 30 or 40 years ago, 70-year-old Liam Neeson would make an odd fit for Philip Marlowe. Raymond Chandler’s L.A. detective, whatever his disposition (and it was frequently not great), was capable of cutting a sprightly figure. This was true in Chandler’s novels and true of most of the great actors who’ve played Marlowe over the years, including Humphrey Bogart, Dick Powell, James Garner, and Elliott Gould. Neeson, even when playing comedy—even when clearing chain fences in thirteen cuts in seven seconds, or whatever it was—has a weight to him that doesn’t let up. In the wrong context, it can lead to performances of lugubriousness rather than gravitas.

But the fact of the matter is that here’s Neeson, 70, reteamed with his “Michael Collins” director Neil Jordan, to play the title role in “Marlowe,” adapted not from a Chandler book but one by John Banville, sanctioned by Chandler’s estate. Set in Bay City, L.A., in 1939, the movie opens with a shot of palm trees against the sun before giving us a glimpse of Marlowe conjuring himself out of bed.

The cutting of a sprightly figure notwithstanding, Marlowe was never a character who was light or meant to be taken lightly. Marlowe does not have joie de vivre. Chandler conceived the detective as a sort of modern-day knight. Behind his ironical observations and biting one-liners, there was a sense not only of purpose but of duty. The old song says a man’s got to be true to his code. Chandler’s Marlowe was; so are Jordan and Neeson. But where other Marlowes in cinema got let off with mere world-weariness, here Neeson sometimes acts as if he’s just been run down by a steamroller.

That’s not a complaint, or rather, it doesn’t have to be. In choosing not to make it one—in other words, by allowing Neeson and Jordan to have their heads—I was able to get a reasonable amount of enjoyment out of this film.

The plot is not of the near-Gordian-knot variety that characterized Chandler’s books. It’s a bit more like, well, “Chinatown,” and the presence of Danny Huston as a transparent—and white-suited!—villain underscores that. Marlowe is approached by Diane Kruger’s Clare Cavendish, a married woman who’s a trifle peeved by the disappearance of her young, movie-industry-affiliated boyfriend. It turns out the guy faked his death; turns out that Clare suspected that but didn’t tell Marlowe when she hired her. Turns out, too, that Clare’s got a dowager-ish mom (Jessica Lange) with an intense interest in her daughter’s personal life and in the life of an ostensible “ambassador” who is himself involved in the lifeblood of a (fictional) film studio.

Add to that Huston’s sleazy nightclub owner, a frightened sister-of-the-not-actually-deceased, an aging starlet with some dope on the not-actually-deceased, a couple of cop friends of Marlowe’s, a side order of corrupt bigwig played by Alan Cumming, and a savvier-than-expected chauffeur (Adewale Akinnuoye-Agbaje), and you’ve got more than sufficient components for a percolating plot.

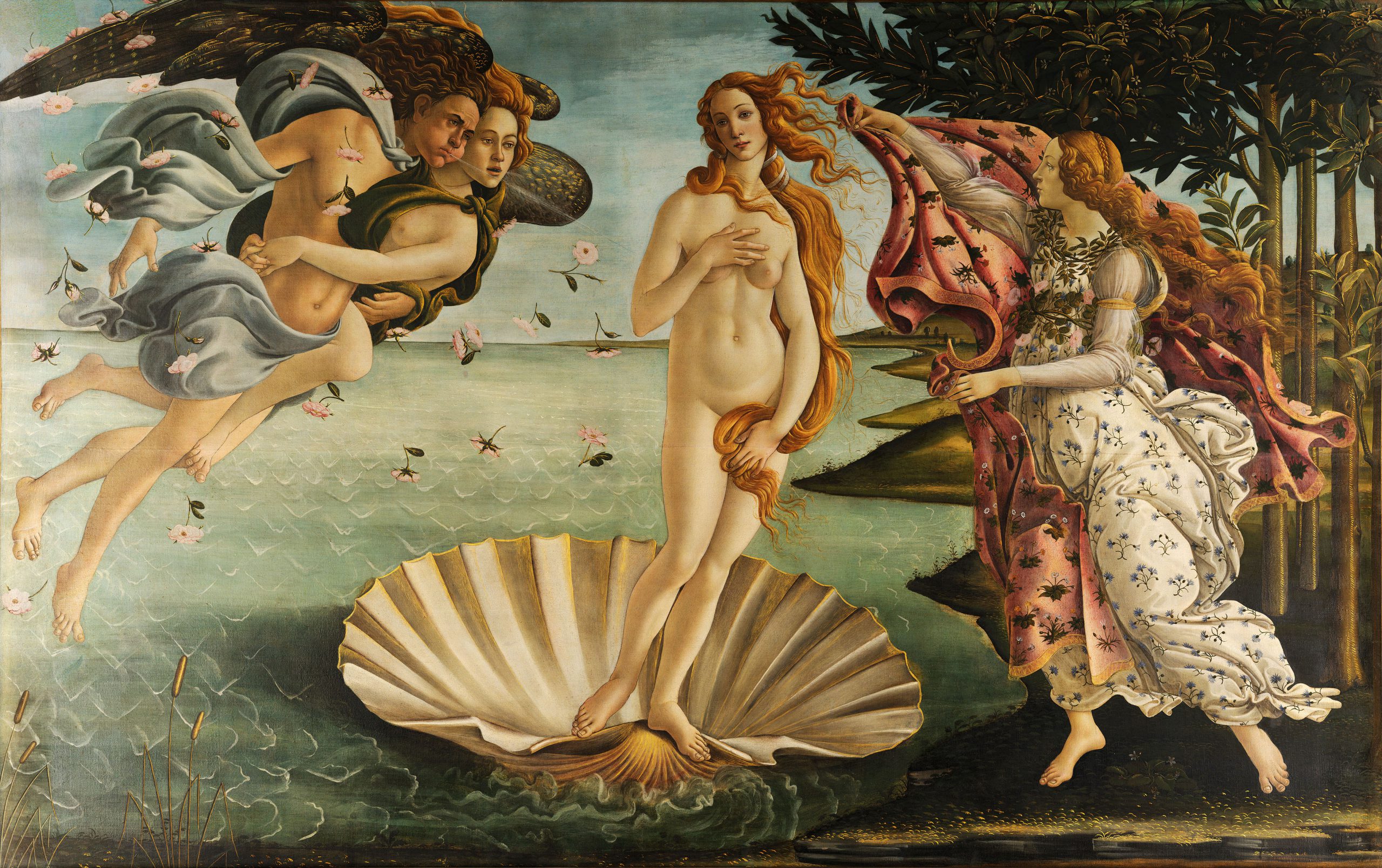

Thing is, “Marlowe” doesn’t do much percolating. William Monahan and Neil Jordan’s script keeps a near-elegiac pace and tone (bolstered and sometimes mildly overthrown by David Holmes’ multi-varied score) as they pepper the dialogue with allusions to Christopher Marlowe, James Joyce, William Strunk, Jr., and Greek myth. He imbues all his characters with a self-consciousness, an awareness that they’re players in a pool of rot, a place some want to wallow in and others want to get out of at least a little clean. Early on, Kruger’s character says to Neeson, “You’re a very perceptive and sensitive man, Mr. Marlowe. I imagine it gets you into trouble.” The remainder of the film is an elaboration of that declaration.

There are quite a few fight scenes, but Neeson doesn’t enter into them eager to show off any, ahem, skills. Before landing a blow, he looks around the room, assesses the situation, and thinks through his opening move as if solving a chess problem. (Which is something Marlowe actually does, both on the page and in this picture.) After one set-to, he observes that, yes, he is getting too old for this. But this cinematic prose-poem contemplates the truth that “too old” also can mean “not dead yet.” And the movie does build up a head of sinister steam, leading to a climactic nightclub siege that’s a riot of colored lights (recalling scenes from Stanley Kubrick’s “A Clockwork Orange” and Martin Scorsese’s “New York, New York”) and grisly corpses.

As for Marlowe’s code, in this vision, it’s open to interior negotiation. At the movie’s end, the detective behaves a little more like a Dashiell Hammett protagonist than Raymond Chandler would think advisable. Revisionist this may be, but it’s done with smarts and, sure … perceptiveness and sensitivity.

Now playing in theaters.