Brie Larson is supremely likable, a trait that has served her well in varied productions from “Captain Marvel” to “Room” and now Apple TV+’s new series “Lessons in Chemistry,” which is based on the popular Bonnie Garmus novel of the same name.

Larson plays Elizabeth Zott, a sometimes wooden but always sympathetic heroine. Bad things do happen to Ms. Zott, as she’s often called, but this is not a dark drama or an antihero tale. The tragedies that befall her are the show’s premise (and predictable even for those who haven’t read the book), but once they’re laid out, creator Lee Eisenberg crafts an aspirational fairytale, building a positively lovely universe and central heroine to spend eight episodes with.

Beautiful art direction is part of what makes this show so pleasant. Like “Mad Men” before it, the mid-century costumes and sets are a sight to behold. From men’s athleisure wear to patterned and high-waisted dresses, the outfits consistently delight in form and function. Little touches like Elizabeth’s subtly changing hairstyles over the years or the shots of her getting ready for bed with her hair pinned transport the audience to a different time. Likewise, the characters live and work in Los Angeles, but it’s different than Hollywood’s palm-tree-lined version. Yes, the skies are blue in “Lessons in Chemistry,” but the neighborhoods are filled with charming bungalows and shade-bearing trees. This was suburban LA before it became the center for car culture and excess.

That said, in Elizabeth Zott’s fictional midcentury California, “sex discrimination” is real and pervasive but doesn’t keep exceptional women down. Zott’s setbacks take her on a decade-long detour from her true dream of chemistry research in the ’50s to being an unexpected TV star in the ’60s, but she never doubts or stops advocating for herself. She calls out sexist practices everywhere she encounters them, challenging the domineering white guys (played by the likes Derek Cecil of Rainn Wilson) whose Y chromosomes have given them unearned power over her. She doesn’t win every battle, but we know she’ll win the war–finding a successful career, modeling the importance of feminine skills like cooking, and decrying antiquated practices like firing a woman outright for becoming pregnant. Those issues may still be with us–one in five mothers today report experiencing pregnancy discrimination at work, for example–but how Elizabeth encounters them makes the issue plain.

Motherhood is a more complicated issue. Early on, our heroine declares she never wants to get married or have kids. And yet, this being TV (or a novel), she finds herself alone, saddled with an unexpected pregnancy. We don’t see her so much as think of terminating (abortion would have been illegal back in the 1950s, but not impossible for a chemist who devises her own pregnancy test using lab frogs). Instead, Elizabeth undergoes the difficulties of her era’s childbirth medical practices and the complications of single motherhood today and always. Here, she finds a common cause with her neighbors, who remember the difficulty of new motherhood, even when wanted and planned for. Eventually, Elizabeth finds joy and encouragement in her role as a mother.

That part is a bit frustrating. Children as learning devices for women is about as tired as rape is as a learning device for men. We need a new narrative that doesn’t make motherhood compulsory for women who don’t want it. Still, it’s nice to see the real challenges of raising children, particularly newborns, taken seriously on screen. It’s a monumentally difficult task and one that is not understood as such (see the erroneous belief that maternity leave is “vacation.”)

In that, motherhood mirrors other feminine-coded tasks of domesticity. It may be hard to dramatize the importance of cleaning or doing laundry, but “Lessons in Chemistry” does an excellent job verbalizing the importance of cooking—stating it often and clearly. Both an art and a science, domestic cooking is the type of work that can feel like drudgery when it’s not appreciated.

But Elizabeth sees and articulates it differently, opening her new cooking show with these words: “In my experience, people do not appreciate the work and sacrifice that goes into being a mother, a wife, a woman. Well, I am not one of those people. At the end of our time here together, we will have done something worth doing. We will have created something that will not go unnoticed. We will have made supper, and it will matter.” With touches like that, “Lessons in Chemistry” clarifies the social construction of gender—too often, it’s the masculine endeavors that we deem valuable, not the thing or the person itself.

Likewise, Elizabeth’s kindness and rationality power the show, particularly as it nudges its characters to improve. Its moral compass is so strong, so clear as to be both reductive and satisfying simultaneously. “Lessons in Chemistry” is largely a morality play where Elizabeth represents the pinnacle of white feminism. She’s smart, determined, courageous, caring, and beautiful, but reluctantly so.

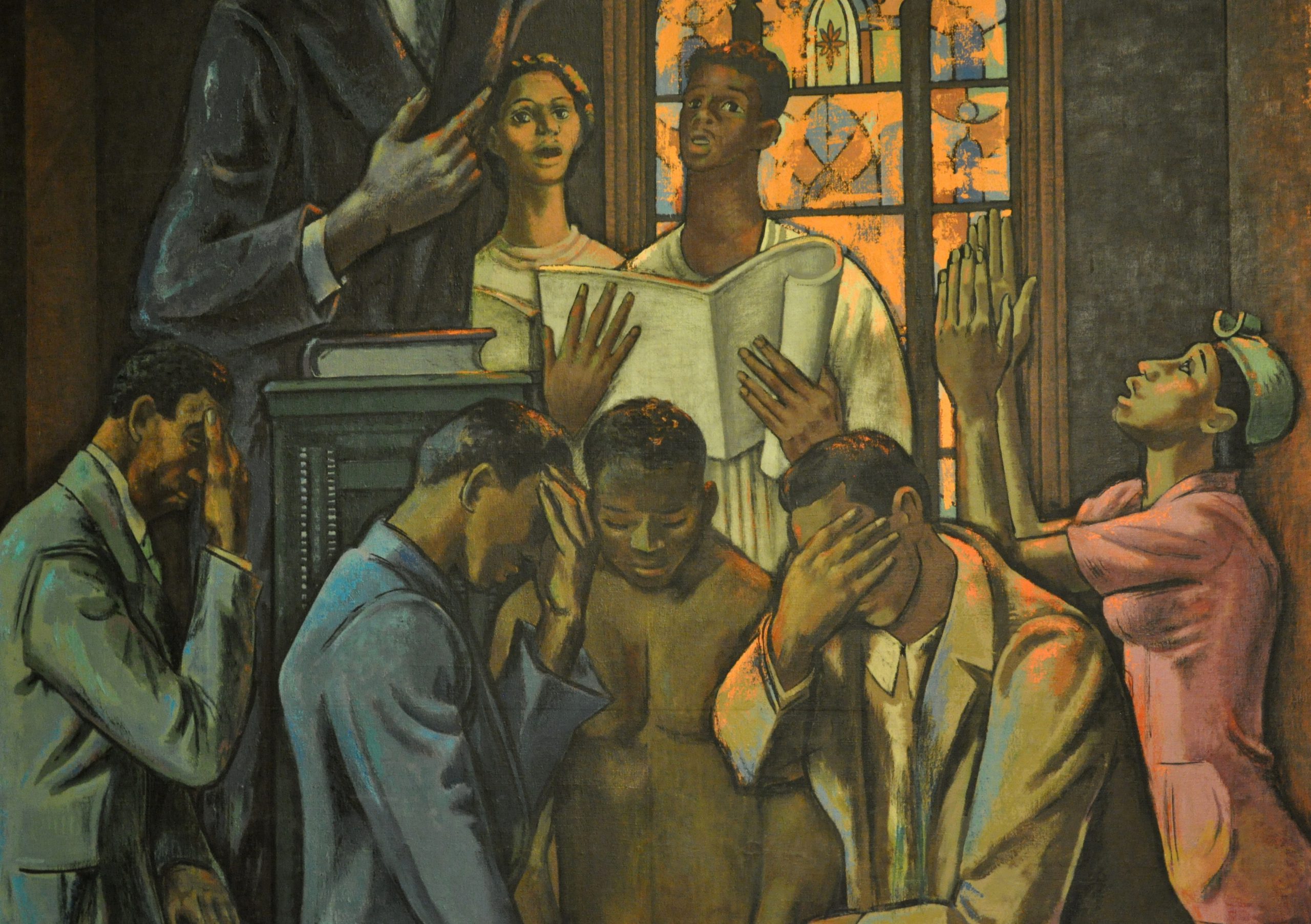

The show is more nuanced with race. When we meet Harriet Sloane (Aja Naomi King), Elizabeth’s eventual neighbor and confidant, we see she is also battling gender norms as she puts her career on hold for her husband. But her larger problem is how the powers-that-be view her mostly Black community of Sugar Hill. She leads the committee to stop Los Angeles building the 10 Freeway to Santa Monica and through her neighborhood. It’s a battle that anyone who’s driven to the beach in LA knows she will lose.

Still, a sit-in scene and Elizabeth’s and Harriet’s reluctant allyship to protect the Black community where they live rings truer than much of the above. It’s not that the gender discrimination of the ‘50s and ‘60s didn’t happen—it’s that the decades-old examples are easy to decry. Would a show with modern examples be as righteous and clear-cut? Probably not. But the show’s handling of police brutality is, sadly, timeless.

It too often feels modern, if not fantastical, that Harriet can prod Elizabeth to recognize and leverage her privilege. Elizabeth grows in the exact right way we in 2023 want her to. She’s a hero, the best possible white woman, a fantasy to aspire to. She may not look like the heroes of comic book movies (but she’s obviously not far off given Larson’s leading work in that realm), but she does offer a blueprint for exceptionalism. Larson’s Elizabeth exists in a world where the right thing to do is always clear if not always chosen.

The cast does a lot of heavy lifting here, too. Larson holds the show’s center with ease, giving way to her supporting cast effortlessly. King has perhaps the most nuanced role, hitting every note, from righteous indignation to playful joy to nudging disappointment. She’s also not stuck as solely a supporting character but rather shines in her own light. The rest of the cast fills out nicely with Lewis Pullman in the dreamy, idealized lover role, Alice Halsey as the believably precious daughter, Kevin Sussman as the overwhelmed producer, and Patrick Walker as the wise friend. Even the dog is perfectly cast.

“Lessons in Chemistry” is a joy to watch, an escape with a clear-cut and righteous perspective. With Larson leading the way, the show challenges us to rise to our best possible selves, even as it presents a simplified view of the challenges women of all races encounter.

The whole series was screened for review. “Lessons in Chemistry” premieres on Apple TV+ on October 13th.