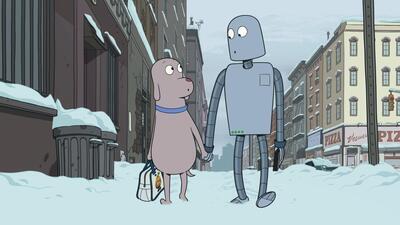

Pablo Berger’s lightly whimsical 2D animation feature “Robot Dreams” will leave you humming Earth, Wind, and Fire’s “September,” though with a feeling in your stomach not usually associated with the dance-ready tune. That’s one of many features of this dialogue-free tale of a lonely dog and the robot friend he purchases, which explores a complicated idea about friendships. It takes place in a 1980s New York City where there are no humans but human-like animals of all types, including monkey punks, snow-diving penguins, and pigs who row boats.

Berger’s story, adapted from the graphic novel by Sara Varon, uses the immediate cuteness of a wholesome, lonely dog looking for a new friend to slowly break down its themes. Its first act is funny and endearing, in which Dog and Robot bond in a series of events often accompanied by the boogie of “September.” Most of all, it is about a connection that can change two souls. No words are used, and it’s easy to imagine how the movie would lose its ability to be projected on if the characters were to articulate their thoughts with words. Instead, it’s in the feeling of how Dog and Robot both, in their own way, learn to smile. Or later on, learn heartbreak.

One fateful day, Dog and Robot go to the beach, and Robot gets into the water, splashing around. Dog doesn’t consider how this could mess with Robot’s mechanics, and it causes him to more or less shut down, although Robot can lie there. The two are then separated by time—it’s the last day on the beach, and when Dog leaves to go get help, he learns soon after that the boardwalk is chained up until next summer. The two have to wait for each other while having different daydreams about their bonds. But they must also be open to the different harmful and fruitful beings who cross their respective paths.

“Robot Dreams” is practically made to be a break for adults from heavier storylines, or in the case of a venue like the Chicago International Film Festival, crushing festival schedules. Its pacing has a welcoming lightness, even when it sometimes can push the limits to how much its respective characters’ daydreams—which hit like fake-outs—can be used. Its 2D style brushes up against the feeling that it’s not advancing the format so much as providing a more adult break from it. Still, the visual contrast is often captivating: the blocky simple construction of the gray Dog, Robot, and other beings, then contrasted with heavily detailed settings down to ridges in junk piles or knick-knacks in a store. Berger’s visual storytelling is assured and compelling enough, especially as “Robot Dreams” offers a more intricate perspective on Dog and Robot’s relationship.

For his latest cinematic venture, the prolific French director François Ozon takes on celebrity and feminism, co-adapting with Philippe Piazza a play from the 1940s written by Georges Berr and Louis Verneuil. “The Crime is Mine,” which will be distributed in the coming months by Music Box Films, is primed to be a crowd-pleaser in how it presents a battle of the sexes with heavy winks and many dollops of synthetic nostalgia. Ozon’s movie isn’t just about an actress who wants to be a starlet in the new era of film sound; it’s also a 1930s comedy through and through.

With a polished presentation that makes it look like one of those fake movies that people in movies watch when they go to the movies, “The Crime is Mine” presents the story of Madeleine (Nadia Tereszkiewicz), who is accused of murdering a grotesque, handsy movie producer. A group of bumbling older men—including lawyers and detectives—are set on taking her down, directly related to their fear of women killing men or of their wives getting a sense that the “men” are not in control. But Madeleine has her lawyer roommate Pauline (Rebecca Marder) on her side, and the two concoct a great speech, playing the men like the sexist, gullible saps they truly are, which keeps her out of jail and makes her a star. Tereszkiewicz and Marder have great fun with the role, shooting dopey fish in a barrel.

The longest-lasting delight in this story (how coincidental that “cream” sounds like “crime” in French) is when Isabelle Huppert shows up as Odette, a gaudy silent film star who has information about the murder. Her hair is outrageous and her voice is pitched over the fence—the chaotic slapstick of Ozon’s film is given another jolt. “The Crime is Mine” is amusing as a twisted mix of feminism, showbiz, and cartoonish personalities, though its immense self-amusement as a #MeToo-era lark can waver on tedious.

From Australia comes “Limbo,” a sullen Outback noir that relies on features from the film genre beyond just its black-and-white presentation. The film is written, directed, shot, cast, and accompanied by the music of Ivan Sen. Simon Baker, who has rarely looked this grizzled and gets some mileage from such a terse performance, is the detective who ventures to a small town full of people who have long held vows of silence about past years. Even when Baker’s Travis comes to this town (and stays at a motel named Limbo), bringing up the cold case of a missing Aboriginal girl named Charlotte from many years ago, people from her community don’t talk.

“Limbo” follows Travis as he goes to one dead end after another while hiding a heroin addiction that we see as his only form of relaxation in such a tense world. He talks to—and drives long distances—to people who knew Charlotte, like her step-brother Charlie (a vulnerable Rob Collins) and Emma (Natasha Wanganeen, who adds fortitude to a role familiar for women in noir films). As Travis navigates this quiet community, his whiteness is a reminder of the unjust policing and poor infrastructure these people have faced. He learns more about a grotesque man named Leon, who used to lure Aboriginal youth like Charlotte to his place to party. Leon is dead and buried, or so his friend claims.

Travis also learns more about why people haven’t shared certain information, and it often involves the cops. The more powerful passages from Sen’s story come from him recognizing the angst of people who have been dehumanized by authorities and live in poverty as their own form of limbo. Characters like Charlie and Emma provide memorable faces to this trauma, but the impact of Sen’s plot-lite script is another story.

Sen approaches the title like a challenge: to make a cold-case mystery about a place and state of mind that has no answers; it all just is. That ambition is intriguing only for so long, as its atmosphere runs monotonous, with repeated stark beats in both editing and dialogue that more or less assert how no one wants to talk, and very little can change. Despite the painterly ways in which the cinematography by Sen uses soft black and white—either in extra wide shots or peeks inside actual cavern abodes—“Limbo” becomes overly sanctimonious in its starkness.