We are pleased to offer an excerpt from the latest issue of the online magazine, Bright Wall/Dark Room. Their theme for this month is “Nostalgia,” and, in addition to Lindsey Romain’s piece about “Barbie” below, includes new essays on “The Big Chill,” “The Grand Budapest Hotel,” “Ghostbusters,” “Memento,” “Chasing Amy,” “Petite Maman,” “Romy and Michele’s High School Reunion,” “The Quiet Man,” “News from Home,” “Between the Lines,” “Of Time and the City,” “Boulevard Nights,” and Audrey Hepburn.

You can read our previous excerpts from the magazine by clicking here. To subscribe to Bright Wall/Dark Room, or look at their most recent essays, click here.

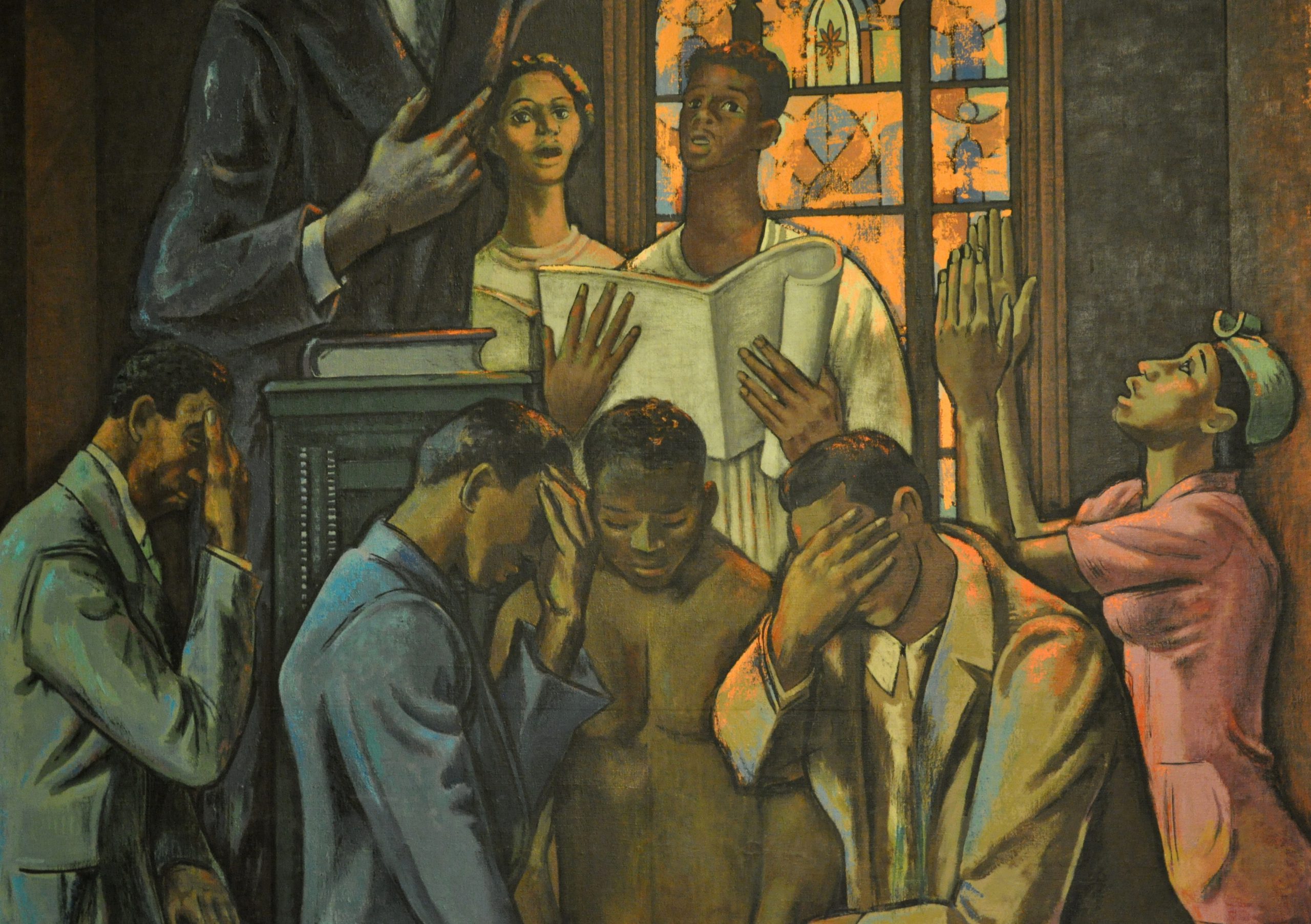

Art Credit: Brianna Ashby

Prologue:

‘S paradise

‘S what I love to see

You’ve made my life so glamorous

You can’t blame me for feeling amorous

“‘S Wonderful,” An American in Paris

Recall Gene Kelly in a paper-labyrinth apartment, a canescent day blinkering through the window, Gershwin melodies mingling with the songs of the street: flute footsteps, string strolls. Lines bending and items chaotic. Every square inch a contraption. Things to pull at and undo: a bed into the ceiling, a chair and table wheeled from the closet, a pitcher retrieved from the porch. Books, papers, pencils askew. In the periphery, a post-war Paris skyline—stony and decayed, transcendently romantic. The past framing the minutiae of a new day, a small life.

Greta Gerwig cited An American in Paris as an influence on her 2023 film, Barbie. It’s an obvious allusion. Not just the apartment but the sketchbook sets, the technicolor, the ferocious imagination it takes to conjure worlds of euphony and play. Childlike, you might say. Remember it? Mine was made of music and carpet, of Barbie cottages and pink plastic shoes, of an indefatigable lust for all things precious: sweets and Christmas and fairy wands and dresses.

This conjures thoughts of my Barbie Fold-Out Family Cottage, released in 1998, confined to grandma’s house where it could be played with on weekends. Its blue PVC walls, accordion-like in how they unfurled. Something tranquil for a child, with all of its little doors and folding beds and white lattice windows. An origami toy box to unleash and live within, not unlike a Minnelli movie. Effulgent colors and memories to be made, to tuck inside an adolescence and retrieve later, when all you want is to crawl back inside of something.

The early moments of Barbie are similarly candy-coded. Similarly Minnelli-esque. A dream house of blush hues, a doll so perfect her teeth glisten and her feet stand forever en pointe. She moves through her day with the ease of child’s play. Clothes magically affixed to limbs. Words spoken simply and phonetically. Friends gathered on lavender sand, waves pristinely and permanently crested, smiles and sun and beach. When Barbie’s friend Ken hurts himself while surfing, a quick doctor’s visit cures him for good. All is well always and forever in Barbieland. It’s Eden—or, perhaps, a playpen. A place where nothing can’t be fixed with a kiss or a mother’s soft hands.

But it’s also synthetic—a resin dream that can only stave off corporeality so long. Isn’t that childhood, too? It’s girlhood almost certainly. Ephemeral and abrupt. Irretrievable once you’ve left it behind.

I.

Girls in white dresses with blue satin sashes

Snowflakes that stay on my nose and eyelashes

Silver-white winters that melt into springs

These are a few of my favorite things “My Favorite Things,” The Sound of Music

Peer through the window and you’ll see a girl—seven, blonde, no front teeth—and her dolls. Barbie Pet Doctor. Babysitter Skipper. Shaving Fun Ken. A smattering of Ariels, red hair blanched from bath water. Some kid-sister Kellys. A few knockoffs too, from the dollar store, Big Lots. Not just dolls for show or hair brushing, but an acting troupe. Vessels to retell the stories of her life and also her favorite movies: Dorothy and friends on a hand-drawn yellow brick road; Victoria Page twirling over a baby-blanket stage; Don, Kathy, and Cosmo singing “Good Morning!” in the tones she can conjure, not perfect but an impressive variety for such small vocal cords.

Her best friend, a boy, lives on the end of the street. He’s freckly and tall for his age. Their moms are close, almost sisters, and so they’re always together, the four of them. He has dolls too but his are dinosaur wranglers and wrestlers and army men. But that doesn’t hinder their play. She makes Muldoon tap dance, and he ties Skipper to the train tracks.

She has a giant personality, loud and magnetic and all-consuming. He is gentler by nature: tender and malleable. His stern father, with his crew cut and farmer plaid, is always upset. At the dinner table, the boy’s eyes brim with tears when his dad gets fired up—about the way he holds a fork, the “prissy” way he eats corn—so the girl squeezes his hand in secret. They are laced together by something unspeakable: born a month apart, friends since she was days old, last names that begin with the same letter so they’re always side-by-side in preschool, kindergarten, first grade. He is the boy but she makes the rules, she always has, and he doesn’t mind much. That’s just the way it’s always been.

They aren’t so different from Barbie and Ken: her in a dream house, him somewhere. Never quite here. Both blonde, sunny smiles. Twinkling. But there is sadness in their stories, too. Tragedy and brokenness in the periphery. Things can’t stay the same. Barbie’s pink paradise and the girl’s childhood—they aren’t bubbles of time but chasms. Something to look back on, not exist within forever.

Barbie learns what it means to die. So does the girl. Perhaps they are intrinsically linked, dolls and death. We bring them to life. We imagine their stories. Dolls are often our first lessons in anatomy and emotion, behavior and expectation. But one day it has to end. One day the music grows distant, the outsidve grows louder, and we set our dolls down forever.

She stops watching The Wizard of Oz and The Sound of Music every day. She has funerals to attend. The boy takes up hunting. The lines in his face grow steady and severe. She misses him profoundly but she can’t say why. The words aren’t quite there—and if they were, she’d be too scared to voice them. Because she’s changed, too. The light has dimmed. Middle school approaches. The real world beckons. But inside of her, buried deep, the sounds and colors still bubble. She tends to them in secret, with show tunes in the car; stuffed animals she buys and keeps under her bed, out of sight; sparkly eyeshadow she wipes off before she goes to school. She moves away, she grows up. But she’s still in that window, too. Framed by light, preserved by memory. Awaiting excavation.

II.

The clock will tick away the hours, one by one

And then the time will come when all the waiting’s done

“I Will Wait for You,” The Umbrellas of Cherbourg

It’s odd to think of Barbie as frivolous when it is in fact deeply rooted in the language of musical cinema—the soft corners of film history. An American in Paris and Singin’ in the Rain, yes, but also Jacques Demy. The Umbrellas of Cherbourg, The Young Girls of Rochefort. Barbie’s hair as precisely and buoyantly blonde as Catherine Deneuve’s. And pinks like you’ve never seen. Searing and impenetrable. Color not in spite of story, but in service of it. Demy made musicals the way a chef might: with precision and order, but delicious mystery, too. He was a scholar of Chaplin, Cocteau, Ophüls. An eye for physicality and humor, as well as construction and locution. Fragrant musical verse that almost purrs. Incantations that unlock whole worlds within us.

Barbie is not entirely a musical. It’s more a patchwork quilt of influence: the scuttlebutt dialogue of Hawks, the quiet sensuality of Almodóvar, the transient yearning of Wenders. But it’s the musicality that brings it to life—that pours soul into Barbie’s plastic limbs. It’s clear that Gerwig has a fondness for lyric and dance; Sondheim plays a pivotal role in her first solo directorial film, Lady Bird, and Frances Ha, which she co-wrote, is about a dancer. But perhaps her affection is less reflex than something inherently, spiritually expressive. Gerwig, always on the brink of tears in interviews, is a familiar sight to Millennial women: full of enormous feeling she can’t possibly contain or comprehend.

The musicality of Barbie only calcifies this. It is bombastic, silly, but also profound. Gerwig plays in that fantastical and balletic sandbox so well. The Matte mauve paintings of Barbieland evoke old school musicals and dance movies: the twinkly blue London and cartoonish sketches of Mary Poppins; the stark, almost startling wide halls and stagey mountains of The Red Shoes; the Emerald City sprawled beyond the poppy field in The Wizard of Oz. The costumes feel like something Irene Sharaff or Gilbert Adrian would have made up, the way they drape and pouf and twirl. And it’s the actors, too. The Barbies and Kens move gracefully through every frame, like a vaudevillian might. Margot Robbie as Barbie doesn’t sing, but her voice is honeyed, cantabile. Ryan Gosling as Ken does, with an effort that recalls Danny Zuko or Curly McLain: fierce, punctuated, slickly boyish—but also pained and pining.

The opening scenes in Barbieland play out like a movie musical might—with an opener that sets the stage. Lizzo sings as Barbie walks us through her morning routine: rise and shine, say hello to friends, get dressed, eat breakfast: “When I wake up / in my own pink world / I get up out of bed and wave to my home girls / ‘Hey Barbie!’ / She’s so cool / all dolled up just playing chess by the pool.” Like Tracy Turnblad to Baltimore or the MC to his cabaret. We know exactly where we are, and thus, exactly what’s at stake.

The dread of the outside world soon creeps in. Barbie starts dreaming of death. Her waffles burn, her milk sours. She learns what she must do: leave this heavenly realm behind to find the girl in the real world who’s playing with her, who is clearly going through it. A Campbellian quest, like many musical heroines must endure: Dorothy Gale, Maria von Trapp, Millie Dillmount . Her sojourn, with Ken in tow, takes us from the artificial safety of Barbieland to the gray, shrill normality of Los Angeles. The music fades. The fantasy dissolves. We are suddenly and somberly present.

But even the shift is of musical legacy. Think again of Demy, and how ardently beauty masks great suffering. Musicals are not just chiffon and eleganza. They are Roy Scheider on his deathbed, singing “bye bye life.” They are María and Tony, ensconced in generational violence, dreaming of somehow, somewhere. They are the longing for someone to hold you too close, someone to hurt you too deep. They are Gene Kelly in a heavenly dream ballet, ribbons of blue and pink distraction (alluded to beautifully in Barbie.) They are revelation and evolution and memory. They are what hurts us most deeply and what can’t be said—only sung, sometimes to no one.

III. Everybody loves a winner

So nobody loved me

“Maybe This Time,” Cabaret

She’s a teenager now, about to graduate high school, and everything is different. It’s funny how quickly it comes on. The violence. She doesn’t feel the full brunt of it because she grew in a little different, her blossoming less elegant than her peers: lumpier, stretch marked. But even that doesn’t protect her. She is startled the first time it happens, coming out of Walmart at night with her best friend. They are sixteen, freshly licensed, reading the back of a DVD they just bought, wearing pajama pants and band sweatshirts. A man—45 or 50—stands in their way. “I’d love to see what’s under those pants,” he says and then licks his lips. He looks like someone’s dad, buttoned up, clean, churchlike. They push past him and run to the car giggling. But the air around them changes the second they crawl into the car. The exchange of something knowing without uttering a word, a new language they will come to know well.

She doesn’t understand the shift at first. Why she is suddenly and always on edge. Perhaps because it keeps happening, little things that remind her she’s entered a new orbit, that she is a fresher and more available thing. There is the time a friend’s dad drops his hand in her lap when he drives her home. The time a teacher, someone she’s known since she was a kid, rubs his finger over hers when he hands back a paper. But even worse—and though she hates to admit—is the other side of it: the men who aren’t attracted to her and who use it against her. The men who were once fatherly and are now dismissive. The more desperate she grows for affection and approval, the more invisible she feels.

It’s awful to move through the day holding onto this. Her existence feels like an apology for a mistake she never made. The clothes she wears, her hairdos, how she walks, where she walks, the exact cadence of her voice—she must be careful not to stand out or offend.

To her horror, she finds her old friend on Myspace. The boy she grew up with. He’s different now. He wears camouflage in his pictures. His profile is full of photos of guns, lyrics to ugly country songs. There’s a .gif of a confederate flag in his bio, rotating on a loop. She hears stories about him from an old friend. How he’s a real piece of shit. Mean, conservative. She once dreamt of reaching out to him, them finding their way back to one another. But she couldn’t handle it—his rejection—so she stayed away. She sees the other boys around her, once friendly and silly and sweet, and how they’ve transmogrified into prowlers. He must be the same, so she must keep herself hidden from them.

Her one respite in all of this is the stage. She’s not particularly talented, but it doesn’t matter much. It’s not the acting or singing or instrument playing that compels her so much as the permeance of theater and music—the community, like found family; the reverence for heroes like Bernstein, Kander, Bock, Menken; the paresthesia that comes from creative work, from painting backdrops, sewing costumes, dance rehearsals, voice training. The way it seeps inside of her and mingles with that vat in her stomach—that place no one knows, that craves ardor, make believe, maybe a little indecency. All of that lush and imaginative energy girls are trained to reign in and silence so they can make room for other things: order, routine, caregiving. It melts away in a spotlight. She’s free in the safe encasement of musical fiction. She remembers her dolls and she feels like them when she’s up there. Shiny, made up, fussed over. Allowed to be anything she wants.

IV.

All I want is a room somewhere

Far away from the cold night air

With one enormous chair

Oh, wouldn’t it be loverly?

“Wouldn’t It Be Loverly,” My Fair Lady

In an interview promoting Barbie, actress America Ferrera—who plays Gloria, the mother of the girl who owns Robbie’s Barbie—spoke of what it means, and costs, to come of age as a girl. In the film, it’s revealed that it’s Gloria, not her daughter Sasha (Ariana Greenblatt), who’s been playing with Barbie. And not just playing with her, but drawing her, dreaming of her, infusing her with insecurities: cellulite, existentialism, death. She and Barbie have become symbiotic, their paranoia lacing.

“Growing up is about leaving behind childish things, particularly for women,” Ferrera said. “Men get to have their man caves and play their video games forever and [for] women it’s, like, toys away, do the chores, grow up. That was really what touched me about Gloria as a character. This woman somehow made it to adulthood holding onto the value of play and the value of aspiration and imagination.”

Much has been made about the film’s faults. It’s gender essentialism, its fatuity, the limits of its feminism. Much about what it lacks, but so little about what it contains. Great, big life. A commitment to the divine, gordian whimsy inside girls. Logic flies out the window at times. In Los Angeles, as Barbie searches for Gloria, she runs through the halls of Mattel and stumbles on a ghostly room where her creator—Ruth Handler—sits with tea. It’s bizarre, almost baroque, but also beautiful in its impossibility. To come of age as a woman, as Barbie does in the film’s middle act, is to cling to magic, wherever it might hide.

Think again of musicals, which so dreamfully interpret this wanderlust. “Hello Twelve, Hello Thirteen, Hello Love” in A Chorus Line, men and women alike lost in the fantasy of puberty—the beauty and the trauma, shifting back and forth in melodic interplay. “Adolesce / too young to take over / too old to ignore / but what for?” Or perhaps Shirley Jones in Oklahoma!, protesting Curly’s fondness for a new girl, pretending she doesn’t care as the resentment boils through lyric. “Many a like lad may kiss and fly / A kiss gone by is bygone / Never have I asked an August sky / ‘Where has last July gone?’”

If girlhood is something like song, then Barbie’s “I Want” song—a great musical tradition—captures this experience as well, growing up from a wistful leitmotif early in the film into a powerful ballad later on. The melody first appears when Barbie encounters Ruth Handler at the Mattel headquarters. In the background, faint piano music, like an old-time radio. It’s actually the chords of Billie Eilish’s “What Was I Made For?”, which plays during Ruth’s introduction first but echoes through the film before coalescing near the end in a triumphant reprise (like many great “I Want” songs do). Gerwig has called this Barbie’s “heart song,” like a lullaby that intones her insecurities and, within them, her hopes.

We go back to Barbieland and learn that Ken has taken over, soured their candy-colored utopia with patriarchy (and horses). Thrown cowhide over pink sofas. And though Barbie, with the help of Gloria and Sasha, is eventually able to overthrow the Ken supremacy and restore balance to Barbieland, her story doesn’t feel over. She’s not quite right anymore. She has seen the real world—she knows too much now. And once you touch it, you can never go back. Once you’re a woman, you’re never a girl again.

Ruth Handler arrives out of nowhere—like Glinda to Dorothy in Oz’s final moments—to tell Barbie she has the power to be whatever she wants. That she can be the dreamer, not the idea, if she only wants it enough. The Eilish cue comes back, boastfully this time, playing over images of real women who Barbie dreams of. The music is compelling, a little haunting, and the lyrics are, too: “I used to float / now I just fall down / I used to know / but I’m not sure now / what I was made for / What was I made for?”

It is a song that, somehow, contains all that Barbie is. An ascent from the innocence of childhood to the pain of adolescence to the existentialism and depression of early adulthood. How boys, our co-conspirators as children, change without warning into strangers, and take too long to discover again, if we can find them at all. (“Don’t ask my boyfriend / that’s not what he’s made for”) How there’s something inherently melancholic and tragic about being a woman. But also how—with nurture, tender reflection—those “faults” can be our weapons. Are what make us whole. Redolent, attentive, maddened, warm. A coarse and varied mosaic. Full of enormous feeling we can’t possibly contain or comprehend.

Think of Holly Golighlty singing about a room somewhere just for her. Fanny Brice, the greatest star. Audrey’s sitcom fantasy beyond Skid Row. Dreams that seem hopeless, reckless, almost crass—but that all come true by the end of their stories. Just like Barbie’s does.

That’s another thing about girlhood. Reclamation of the nostalgia not afforded to you. Asking for it back—or creating it anew, if that’s what it takes.

Barbie may not sing her own “I Want” song, but that’s the beauty of musical logic. There is no logic. It’s trancelike and unassuming. A whisper in the head. A reverberation, a palpitation, a wish. All that matters is that it states, in some transient way, what cannot simply be said. A thought so impervious, only song might ignite it.

The End. I’ve got a beautiful feelin’

Everything’s goin’ my way.

Oh, what a beautiful day

“Finale: Oh, What A Beautiful Mornin’,” Oklahoma!

She is almost 35 now. Her twenties flew by chaotically and in many ways regrettably. She’d change some things if she could, thinks it’s silly when people say they wouldn’t. But here she is. Abundant. Alive. Much has settled, but she realizes—with warmth—that life is never quite done. You keep picking up, you keep fiddling. You find your way.

Recently, she has taken to long naps on her porch. She stays up a little too late. She buys things on instinct. One day, it’s a velociraptor toy in the sale aisle at Target. It makes her think of her long-lost friend, the one from childhood who still tiptoes through her memories. She found him again on Facebook. He seems a little better now. Less riled up. He bought his childhood home from his parents. He’s married. He still hunts, but that doesn’t bug her so much. One day her face lights up when she sees him in a photo with his father, who commented under it, “I’m so proud of my son.” She remembers that things can change.

She puts the velociraptor on her desk and stares at it fondly while she works and writes. She does more of that these days—writing. She sings, too. Stands in her living room and just belts. It feels good. Like a cleansing. She imagines herself in Gene Kelly’s Paris apartment, or her Barbie Family Cottage, or her old house, framed by that dormer window where she sat and played with her dolls. But escape holds less appeal these days. She’s realizing, more and more, that she’s quite content where she is. That thing she tried to contain? She doesn’t have to anymore.

At night she watches videos on her phone of girls coming out of the Barbie movie. Many are crying. There’s a speech in the film that Gloria gives to Barbie—about all that women contain, all the expectations foisted at them that they can never live up to. It’s nothing new, but watching it does something to these girls. It evokes an empathy for their past selves. When they first found out what it means to grow up, the cost of it all—what you lose and forget. They cry because it hurts to see Barbie learn this too, but also because there is solace in remembering. It kindles something. They start buying dolls again. They resurrect those lost strands of imagination. They want to create and live wildly again.

She smiles as she watches along. She feels it too. Something swelling. She puts down her phone, smiles at the little trinkets around her, the life she’s built for herself, in spite of it all: the pain and tragedy, the never-ending reevaluation. It’s her story, the one she’ll keep writing about, telling—that she’ll pass on. In the far-off distance she swears she hears a clatter of paper and strings, the soft tuning of instruments. A new overture is about to begin.