While HBO fans are understandably in the vice-like grip of “Succession” fever the last few weeks (and justifiably so, considering the bone-shaking highs of its most recent episode), it’s easy to forget that one of its best shows is also undergoing a fourth and final season this month. “Barry,” the impeccable dark comedy from Bill Hader and Alec Berg about a hitman grasping onto normalcy through the absurd dream of an acting career, has only grown more complex as its run has continued—morphing ever so gradually from “Get Shorty” to “Breaking Bad” with each new season. And in its closing chapters, “Barry” grows ever closer to Vince Gilligan’s ruminations on the inextricable links between ego and violence, in ways that may just surprise you.

Piggybacking off last year’s tense season finale, season four opens with Barry (Hader) in prison for his crimes—not just any prison, but one that also houses his former handler, Fuches (Stephen Root), who grows desperate for protection from the Feds once he finds out. But Barry’s not interested in killing him anymore; he’s rudderless after discovering that his former acting teacher/father figure, Gene Cousineau (Henry Winkler), sold him upriver for killing his girlfriend at the end of the first season. “Mr. Cousineau, are you mad at me? Because I love you,” Barry whines helplessly into a prison payphone early in the season, his pleas falling on deaf ears. Hader’s always been skilled at walking Barry’s delicate tightrope between a hardened psychopath and a lost little boy, and his time in the clink unearths new layers of vulnerability.

But as broken down as Barry has become, the aftereffects of his actions over the first three seasons have rippled through the show’s supporting cast. Even outside its title character, “Barry” has always been about the innate push and pull between transgression and redemption, the ways we use our pain and resentment as fuel for creativity.

Those contradictions are fundamental to what makes the show so damn watchable. Take the very first minutes of the show—an extended wide shot from inside a prison guard office, tracking Barry as he walks to his cell. We hear the guards chattering about him from offscreen: Yes, he’s the Barry Berkman, the brutal murderer brought to justice. “He’s on f**king TV!” the other guard gushes; even in prison, you can’t escape the pull of celebrity. It’s a level of grace Barry neither desires nor deliberately attracts. He sees prison as his penance.

Indeed, much of the first half of “Barry”’s final season is about our characters running from their true selves that the first three seasons revealed in all of them. Sally (Sarah Goldberg) flees to her hometown of Joplin, Missouri, where his parents seem less concerned with her former boyfriend’s status as a murderer than all of the self-mythologizing she did in her semi-autobiographical streaming series. Meanwhile, Gene professes a humble desire to see justice done but can only express that desire in ways that put eyes and attention back on him. Like Barry, he seeks absolution for his sins and further collapse when no one can give it to them.

The closest anyone in the show has come to a happy ending is NoHo Hank (Andrew Carrigan), everyone’s favorite Chechen criminal hype beast. Having broken his Guatemalan crime-lord lover Cristobal (Michael Irby) away from his homophobic family last season, they’re clamoring to go straight—right down to a hilariously offbeat sales pitch to their former gang members amid the neon lights and jalapeno poppers of a Dave & Buster’s. But Hank’s mind still reels with thoughts of Barry, whether as a prospective ally or a liability who could rat him out. Everyone, even the happy-go-luckiest of the cast, are still looking over their shoulders, just waiting for the other shoe to drop.

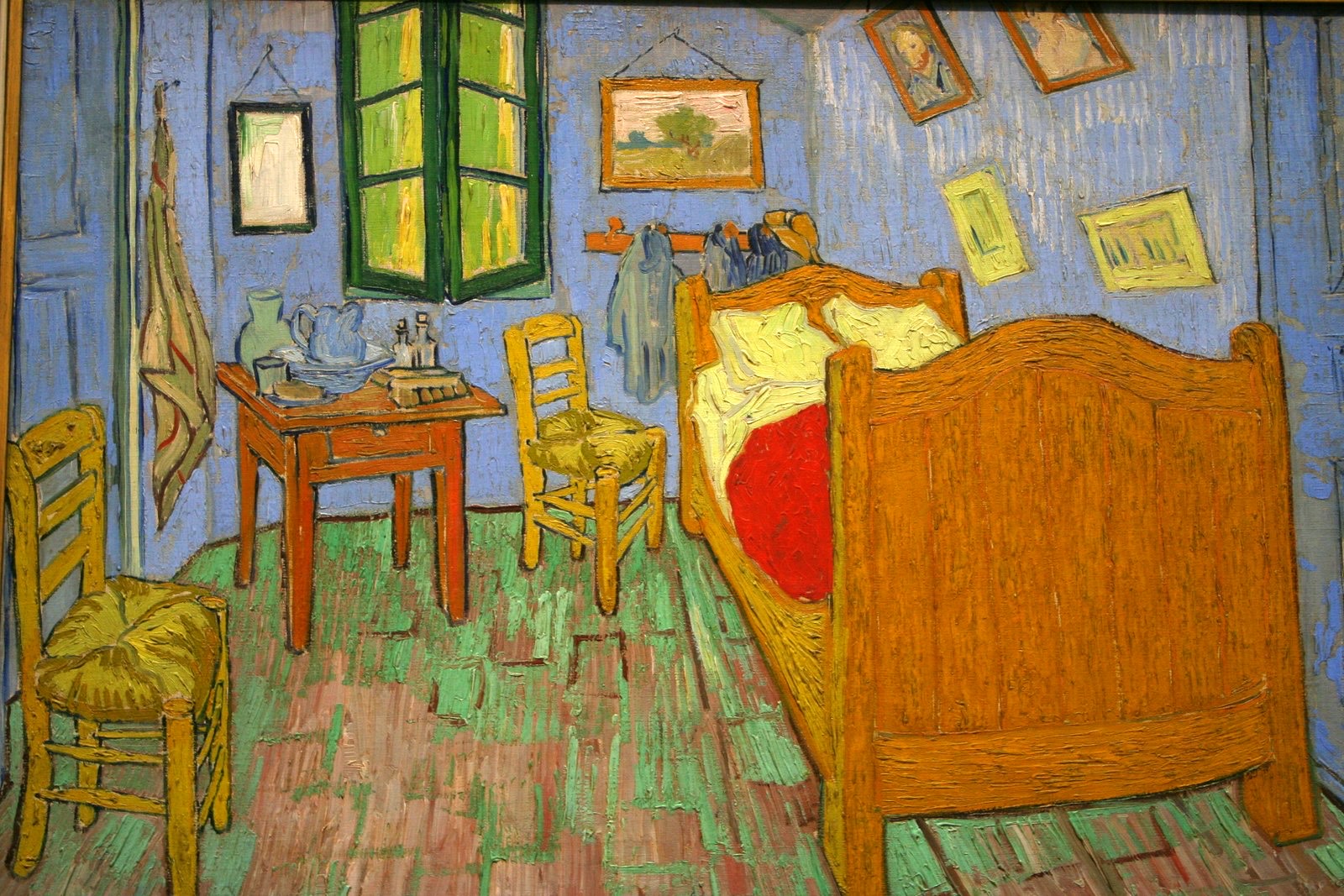

Hader directs every episode this season, and it’s thrilling to see how much he’s grown as a filmmaker. He has a master’s command of blocking and pacing, each episode an exercise in prismatic stillness, often giving way to explosive violence. The smooth camerawork and locked-in compositions are downright painterly, further emphasizing each character’s inner turmoil. The world around them is stiff and unrelenting, and everyone, from Barry to Hank to Sally, yearns to break free from the cycles they’ve found themselves in.

That’s not to say the show has lost its bone-dry sense of humor, as its cheekily-staged action setpieces and breathless comic energy can attest. It hasn’t even stopped taking acidic potshots at the vagaries of show business: The indie-darling-to-superhero-schlock industrial complex, the wide gulf between hot people who look good in Spandex and “real” actors, the voyeuristic pull to turn every horrible tragedy into a scintillating true-crime thriller. And atop all that, the narcissism that draws everyone into Hollywood’s orbit, no matter how deep they think their principles may be.

The first half of “Barry”’s final season contains all of this, to say nothing of the astonishing, surprising way Hader and Berg bifurcate the season—a move that’ll send the “Breaking Bad” comparisons rocketing into orbit. It’d be downright criminal to say anything more, but suffice it to say episode five contains game-changing work from both Hader and Goldberg (the former as a director, especially), and it just gets more surprising from there.

“This is not a good guy-bad guy story,” Gene confesses to a character late in the season about his deeply flawed, parasitic relationship with Barry. Fittingly, it serves as a thesis for “Barry” as a show: Cold-blooded assassins can contain multitudes of anguish and relatable loneliness, and even the most innocent of us have hidden seeds of darkness within them, just waiting for the right climate in which to sprout. It’s hardly the original premise, but it’s hard to think of a show that explores it with as deft and devilish a hand as “Barry.”

Seven episodes were screened for review. The final season of “Barry” premieres on April 16th.