The Criterion Collection may have surprised some collectors when they announced last May that they would be releasing two Albert Brooks movies on their label in August: “Real Life” and “Mother.” “Real Life” was not a surprise. An HD treatment was long overdue and had been a favorite for so many Brooks fans and fans of comedies that seemed ahead of their time. It’s a movie lover’s movie and Criterion’s acquisition of it was a natural choice. “Mother,” though, seemed to come out of left field. His 1981 romantic comedy, “Modern Romance,” a film that is as much about movies as it is about relationships, would have been the more predictable choice. It’s also long overdue for an upgrade (please, we’re all dying to get rid of that horrific DVD cover Sony put out a couple decades ago).

Whatever the reason, there exists connections between “Real Life” and ”Mother” that I never considered until now (aside from both being from Paramount). This dual Blu-ray release gives viewers a chance to explore Brooks’ work from two completely different points of view. “Real Life” takes a satirical approach to the virtues of documenting reality and giving commoners a chance to be the stars of their own movie. It gets laughs by putting everyone in an uncomfortable situation where some of the participants (namely Brooks) remain stubbornly unaware of the consequences of their actions. “Mother” is less conceptual, a far more personal and sentimental film from a much older Brooks, who mined his relationship with his own mother for comedy and came up with a revelation that audiences could emotionally connect to, much more than an experimental fake documentary.

The simplest connection between the two films is they are both about family dynamics and what happens when someone intrudes upon a household and, essentially, takes it over. One film explores the theme on a grand scale (“Real Life”), the other more intimate (“Mother”). They are the only two films where Brooks has ever explored families and how they function or not function. Brooks has two children of his own, but he has never made a movie on the subject of child-rearing or parenthood where he is one of the parents (oddly enough, the role for which he is most famous is the voice of Marlin, the father in “Finding Nemo/Dory”). In “Real Life,” he’s the outsider peeking into the lives of a typical suburban family hoping to score documentary gold. In “Mother,” in many ways, he’s still an outsider, except it’s his own mom who has no interest in having him stay in her house, reassembling his childhood bedroom or going about the business of figuring out his relationship with her. Brooks is only begrudgingly accepted into both of these households.

In his debut film, “Real Life,” Brooks stars as a different Albert Brooks, an ambitious filmmaker and comedian setting out to make a movie about reality, focusing on an average white family in Phoenix named the Yeagers–in one of his best performances, Charles Grodin plays the terminally awkward Warren and Francis Lee McCain beautifully provides the voice of reason and skepticism as Jeanette, the more down-to-earth mom. Brooks’ character keeps bragging that his project has enough integrity and innovation to win not just an Oscar, but also a Nobel Prize. At every turn, though, Brooks’ character keeps getting in his own way by putting ego ahead of the artform and shunning scientists working with him who warn that he is getting a false reality with this film.

Forty-five years after its release in 1979, “Real Life” remains a visionary comedy masterpiece. Its prophesying of digital filmmaking technology and reality TV has been well documented. One can still watch “Real Life” and marvel at just how on-target Brooks’ film had become while still being among the funniest films ever made. Every time one of those goofy looking, white pull-over Ettenauer cameras is seen in the background or hearing one of the poor cameramen talk through it and sounding like they’re trapped in a plastic egg is a highpoint of absurdist comedy, but at the same time, don’t we look pretty silly today talking to someone in public who is not in front of us?

One could easily trace “Real Life”’s satirical vision of suburban America to “The Simpsons,” which would start its legendary run six years later. Brooks co-wrote the film with Monica Johnson and Harry Shearer, who would go on to provide at least twenty voices for “The Simpsons,” which was co-produced by James L. Brooks, who has a cameo in “Real Life” as a driving instructor. He and Brooks would also work together on “Modern Romance” and “Broadcast News.” In between that, though, is the very similarly themed limited series from 1986 called “The History of White People In America,” by the late, great Martin Mull. The show took a few pages out of Brooks’ idea, but had a personality all its own. The show still comes highly recommended, especially for fans of Fred Willard. Closing the circle, Shearer worked on that show as well.

Much of the bonus material on Criterion’s disc touches on the inspiration for “Real Life.” the PBS documentary series “An American Family,” which premiered six years earlier (as does the terrific essay by A.S. Hamrah). I don’t know if any effort was made to try and secure some footage from the show to present here, but I would have loved to see some episodes or clips. I could only find a few bits and pieces on YouTube.

“Real Life” has always been my personal favorite Brooks film, especially after having worked on a couple documentary projects myself. No documentary filmmaker wants to admit it, but Brooks’ character’s antics in the film have an uncomfortable reality to them. Just watch the scene between him and Grodin when Warren Yeager, a vet who just lost a horse on the operating table, begs Brooks to not include the scene in the final film. Brooks, knowing he hit the jackpot with this scene, brushes off the concern and insists it’s great for the film because it’s real, never once allowing for consideration of Warren’s reputation or future prospects. There are many filmmakers out there who insist, “no matter what, never, ever turn off the camera.” We, as viewers, often accept that, since it makes for compelling cinema, but there remains an unspoken behind-the-scenes discomfort with everyone involved that we rarely ever see (Steve James’ “Stevie” is the first film that comes to mind where the director bravely puts himself in the hot seat for the film he’s making). This dialogue exchange in “Real Life” sums up the documentary filmmaking experience better than anything else out there:

Jeanette Yeager (not feeling well, getting into her car): “I just want to be alone right now.”

Albert Brooks: “Okay, can we come with you?”

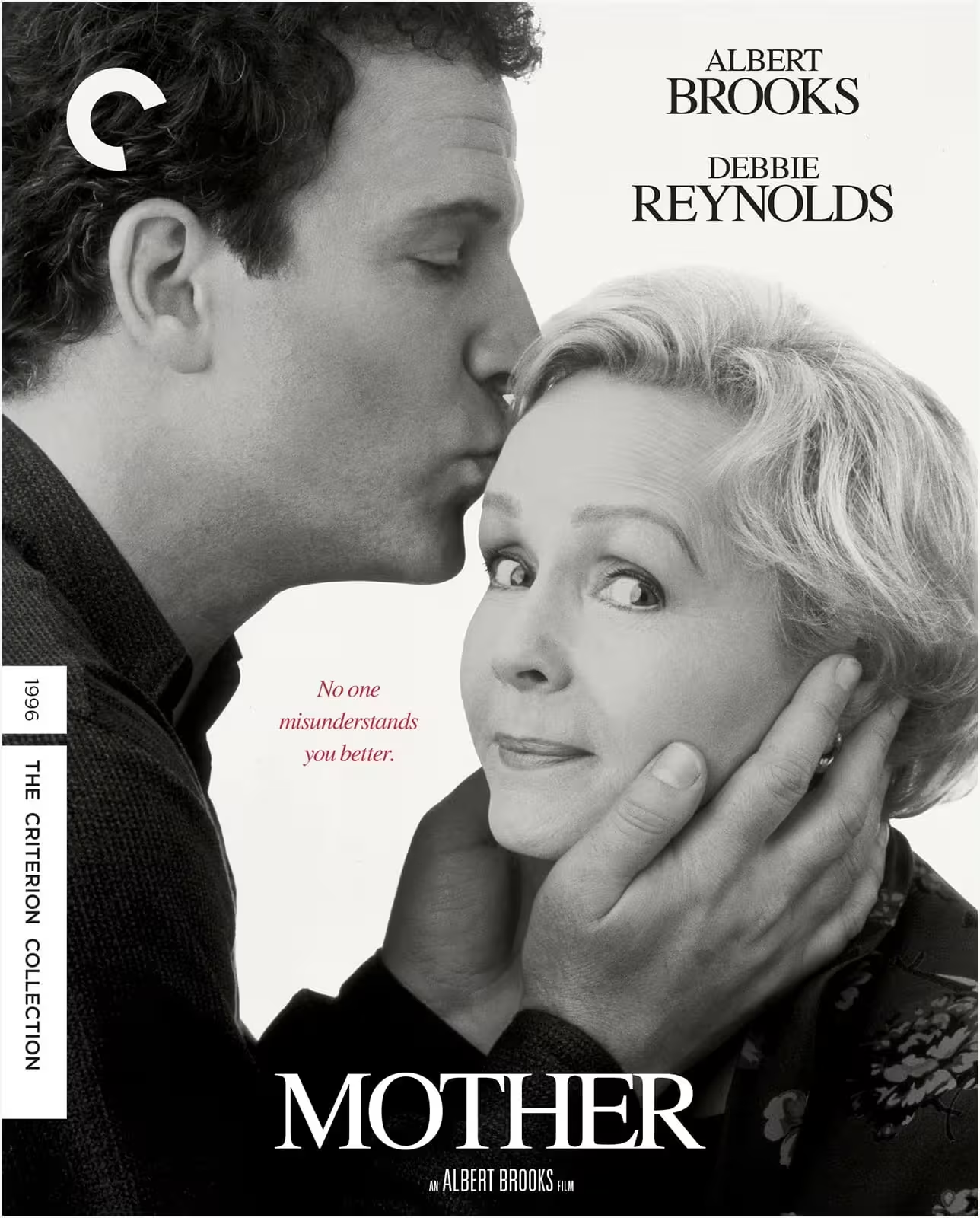

Released in 1996, “Mother” is a softer and more personal film for Brooks. It opens with his character, a science fiction writer named John Henderson, getting divorced and being forced to confront why he’s had two failed marriages. Surely, it must be because of his relationship with his mother, Beatrice, played by Debbie Reynolds, whose legendary status as one of the great all-time entertainers is practically unrecognizable here, playing a mother we’ve all known and whose vulnerability is shielded by decades of long-buried resentment and her daily routine of buying only the cheapest of food items at the grocery store. John moves back in with her as “an experiment” to try and figure out why his mother seems to consistently disapprove of his life choices over the years, but never criticizes his financially well-off and highly accomplished brother, Jeff (Rob Morrow). John and his mother go shopping together, go out to eat and take trips to the zoo and it becomes very clear they do not understand each other.

While John goes through his one-sided therapeutic process, he becomes plagued with writer’s block. Being a science fiction writer who creates worlds with aliens and monsters with big heads and little brains unconsciously becomes part of the divide between him and his mother. She can’t relate to that sort of thing, but as we later learn, she herself was a writer at one time, focusing on real life stories from personal experience. In “Real Life,” Brooks’ character is after reality in his chosen art form and ends up with something hopelessly manufactured. In “Mother,” John tries to manufacture a world, but reality gets in the way. At one point, after he makes a wisecrack, his mom says “if only your writing were that real.” More often than not, Beatrice won’t listen to what John is trying to tell her, just as in “Real Life,” Brooks won’t listen to anyone telling him he’s going about this project all wrong. Both films have conflicts rooted in the breakdown of communication.

Speaking of communication, Roger Ebert once said that nobody has better phone call scenes in movies than Brooks. “Mother” takes his trademark phone call scenes and updates them for modern (at the time) technology. Beatrice cannot figure out the call-waiting feature on her phone, but even funnier, her other son, Jeff, insists she use the video feature on her phone so they can see each other when they talk. The results find Reynolds giving a hilarious physical performance as she contorns her body to make sure her head can be seen on screen. As a bonus feature, Criterion includes a teaser trailer for “Mother,” that is essentially a one-sided conversation Brooks is having with his own mother, but tying it with the then-current “Mission: Impossible” movie. Another trademark Brooks scene is him telling everyone he meets about his problems in life, but in “Mother,” the table is turned. In “Lost In America,” he tells every sales clerk he and his wife dropped out of society, as if they would care. In “Modern Romance,” he tells everyone about his break-up, as if they would care. Here, his mom tells every sales clerk about his personal life and he takes offense.

Both “Real Life” and “Mother” are quintessential Brooks films. One represents his conceptual side that harkens back to his days on “Saturday Night Live” and the talk show circuit. The other is the storyteller using real life situations and having himself as the unwitting victim of circumstance. Both discs have insightful, entertaining interviews with Brooks, McCain (“Real Life”) and Morrow (“Mother”). I’m sure “Modern Romance” will have its day in HD. If not from Criterion, maybe Sony will make it happen since they’ve been steadily releasing films from their back-catalog with some surprising results (just speculating here. I have no insight into any of this). There’s also “The Muse” and “Looking For Comedy In the Muslim World” to consider as well. Whatever the case, we’re lucky to have these two titles available and to look at them and wonder, “Would my family make for an interesting documentary? If not, am I to blame? Or my mother?”

(My mistake. “Modern Romance” is available on blu-ray from Sony, although it took a little digging to find the page and it initially did not come up at all when I searched for it originally. Still, it’s not unusual for Criterion to release their own edition of a film that already has a Blu-ray release)