Alex Cox burst onto the film scene 40 years ago with “Repo Man,” a science-fiction satire starring Emilio Estevez and Harry Dean Stanton, with a theme by Iggy Pop and a soundtrack heavy on punk rock. He went on to make the music biopic “Sid & Nancy,” the modernized spaghetti western “Straight to Hell,” the political satire “Walker,” the minimalist character study “Highway Patrolman,” the Jorge Luis Borges adaptation “Death and the Compass,” and the Jacobean-styled “The Revengers Tragedy,” loosely adapted from the same-named play. With each new project, Cox moved a bit further outside of the mainstream. He hasn’t made a traditionally funded independent film since “Revengers” in 2002.

Cox’s latest is a crowdfunded project that ends its Kickstarter campaign July 29. Though puckishly titled “My Last Movie,” it’s “a Western adaptation of Nikolai Gogol’s Dead Souls which takes place in southern Arizona and Texas in the 1890s and will be shot in Spain and Arizona, and it’s a super low-budget film.” It’s his third crowdfunded feature in the last 20 years, the other two being “Bill, the Galactic Hero,” based on Harry Harrison’s novel, and “Tombstone Rashomon,” which retells the story of the gunfight at the O.K. Corral from multiple perspectives. I talked to Cox about the new movie, the evolution of independent filmmaking during the last four decades, and his definition of the word success.

So, how literally are we supposed to take the title “My Last Movie”?

Well, I mean, it could be my last movie. I haven’t made a movie for nearly 10 years, you know. In another 10 years time, I’m going to be nearly 80. So there’s a possibility that it will be my last movie.

The original funding goal was $75,000. And you’ve exceeded it, right?

Oh, yeah. That [budget] was to make the film with glove puppets. If you have real actors, you have to pay them more.

What was it about this material that appealed to you?

It’s just a great story. It fascinated me that Dead Souls is the first part of what Gogol intended as a trilogy, but he could never even complete the second book. He destroyed the second draft [of the second book] multiple times and never even got into the third draft. There are fragments of the second draft, including the miserable childhood experiences of the protagonist, which are just great. and we’ve included those in the script as well.

How do you transplant an 1842 Russian novel to the United States and turn it into a Western?

The book is about a man who is acquiring the names of dead serfs. The book was written during the [era of] serfdom, which I guess you could say was equivalent to slavery and that still existed in Russia when Gogol wrote the book. The year that the the American Civil War began, serfdom was abolished in Russia. So Russia actually preceded the United States in abolishing slavery by a few years. At the time that serfdom existed, it was possible to acquire a large number of serfs, and if you acquired enough—I don’t know exactly how many you had to have—you could be an aristocrat of sorts. Maybe you’d even be a prince, who knows? And so the protagonist of Dead Souls, Chichikov, is acquiring serfs. but because he’s doing it on the cheap, he’s actually acquiring the names of dead serfs, who he then going to present to the requisite authorities in order to acquire glory in Czarist Russia. My protagonist is acquiring the names of dead Mexicans, because he has a way of turning the names of dead Mexicans into money, or thinks he does.

Interesting. I can already see that this unmade project has a lot of similarities with previous work that you’ve done, including the sort of purgatorial aspect that some of your some of your films have, and also the sense that morality is merely an abstract construct for a lot of people.

When Gogol was trying to go about writing the three books, the first one was supposed to be about bad people, the second one was supposed to be about good people, and the third one was supposed to be about paradise. But he couldn’t even get the second one completed, because it’s much easier to write about bad people than good people. It’s also more entertaining and much more dramatic. And imagine writing about heaven—how boring that would be, you know?

Hell is definitely more cinematic.

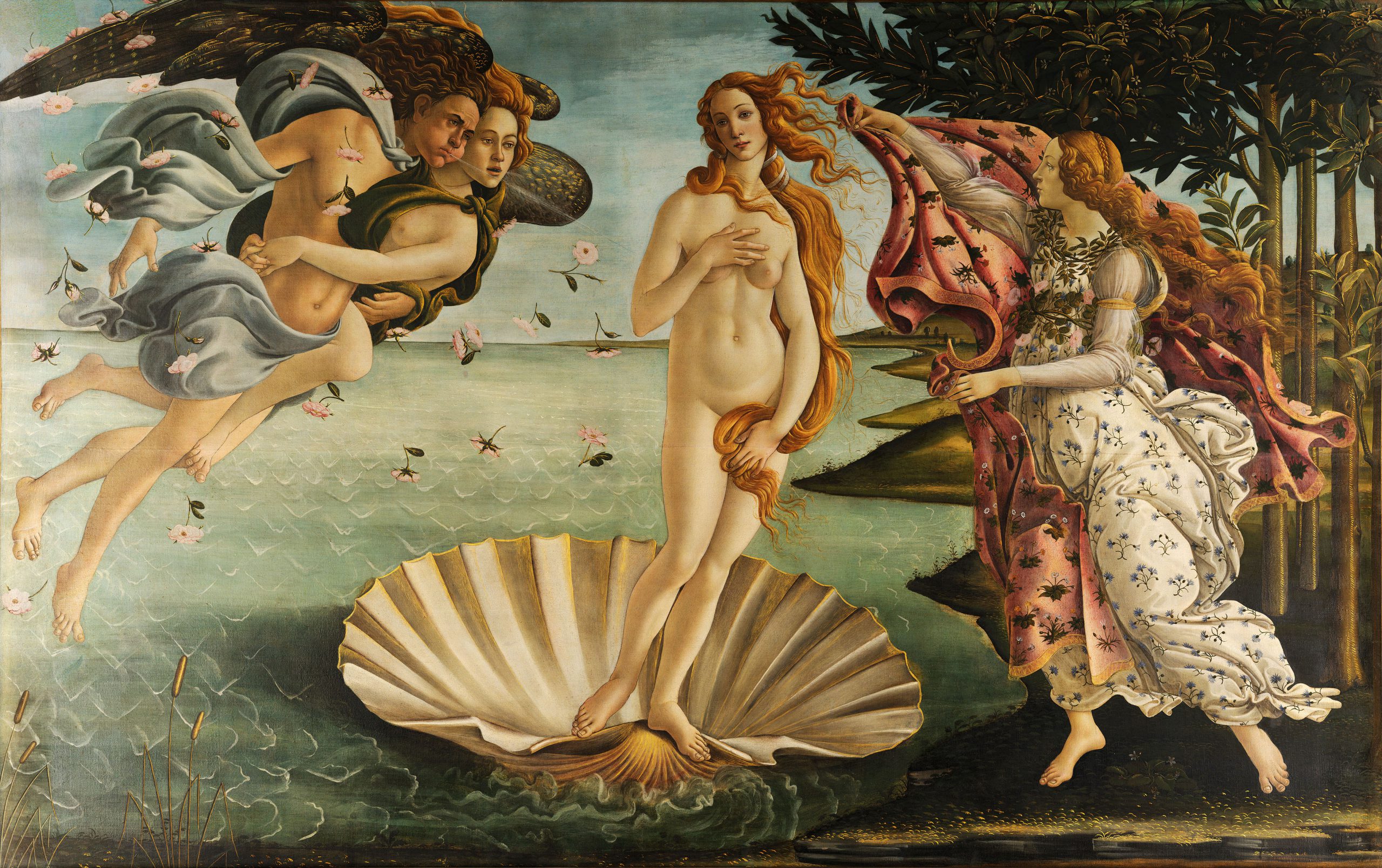

And more literary as well. It’s more interesting and more painterly. I mean, there are lots and lots of paintings from the Middle Ages about Hell, but there aren’t as many paintings of heaven.

How long did it take for you to decide, ‘I’m going to have to fund these movies some other way, because the system as it stands is not giving me what I need”?

It used to be back in the olden days, 20 years ago or more, you would fund a film from sales. You’d make a domestic sale and you’d make foreign sales. You’d do this via a sales agency. Sometimes, you know, a production company or a studio would fund the film and then distribute and then and then sell it later to a distributor. But that model of funding films seemed to become increasingly difficult and increasingly rare and also very anodyne. The type of films that were getting made via that model. tended to be romantic comedies, and romcoms didn’t seem like a very interesting possibility to me. And then my friend Phil Tippett crowdfunded the first third of his film “Mad God” and I thought, Wow. When Phil did that, I thought, This is the way to go.

You had a kind of a remarkable and in some ways unlikely run in the’ 80s and’ 90s where you were able to get these really uncompromising films funded and seen. What has changed to make it harder?

The early ‘80s was kind of the end of the ‘70s, and the ‘70s was the continuation of the ‘60s, and there was still a movement of independent film then. In those days, there was what they called the New American cinema, which included people like Monte Hellman and Dennis Hopper and Bob Rafelson and Hal Ashby. There were these very, very interesting films being made often by American directors and their equivalents in Europe, and also in Britain, with people like Lindsay Anderson. It was a fantastic time to be making films. And at the time, conventional entities like studios and television companies were interested in making feature films.

But another thing is, when I was doing them back then, they were negative pickups for the studios, and the studios didn’t have anything to do with the production of the film, and that was part of the appeal as well: it was a way for the studios to get certain kinds of films made but avoid working with the unions. I mean, we didn’t think of ourselves as union busters when we were making “Rep Man,” but we were. The negative pickup deal was also a way for [studios] to learn how to make ‘independent films.’ Universal would then go on to invent a thing that was like an independent film company—called Focus Features, say—which was totally studio-owned but made ‘independent films.’

Then the industry changed, because once the studios figured out the mechanics of making a lower budget independent film, the last thing they wanted to do was work with independent filmmakers, you know, because they much prefer to work with dependent filmmakers. Then independent filmmakers went off on a different route, and for a little while films were funded by record companies or by TV companies. Then we went the route of trying to divide the cost of the production between the domestic production company or distributor and foreign sales. When that dried up, then came crowdfunding.

I’ve seen a lot of really interesting super low-budget films in the last decade or so, but it seems like their problem is always getting seen. How do you break through the noise?

I wonder as well. The means of production are within the hands of the filmmaker now that we can shoot on video rather than on celluloid. It’s much cheaper to make a film in that sense. But distribution is another matter. You know, I made a film for Roger Corman called “Searchers 2.0” and Corman had plenty of money, but he didn’t have a distribution company. Distribution of the finished film was dependent on who Corman could find to distribute it.

I remember that one. It was made for, maybe not used-car prices, but trailer home prices.

Yeah, yeah—I think that one was done for about $200,000. That is because $200,000 was the [Screen Actors’ Guild] super-low budget level. If you wanted to get SAG actors at the lowest possible rate, then your budget couldn’t exceed $200,000, and so that became the top level for super low-budget films.

What are you doing at the moment, just as your regular gig?

Oh, I don’t have a regular gig anymore! I mean, I never really had a regular gig at all. Except when I was teaching at Colorado University-Boulder—that was a regular gig. I taught at CU Boulder for four years. That was the only full time job that I’ve ever had. Everything else has been project by project. Sometimes I do commentaries for DVDs or make little videos to present DVDs. For a while, I was introducing films on the BBC in England. But I’ve never really had a proper job. My wife made me get a job at CU Boulder because she said we needed to make money, we needed to have a regular income, and I could only think of two jobs that I was capable of doing. One was a gas station attendant and the other was a university professor.

What’s happening with the “Repo Man” sequel that we heard about earlier this year?

Oh, I’ve been doing that for a long time. Every 10 years I write a new script because every 10 years things are different. This is like the fourth “Repo Man 2” that I’ve written in the last four decades. And I’m still trying to raise money for it. The producer is Lorenzo O’Brien, who produced “Walker” and who wrote and produced “Highway Patrolman.” He was also the producer of the series “Narcos.” The lead actor, if we’re able to get him, is Kiowa Gordon, who I like very much. We are constrained by only having the domestic rights to the United States “Repo Man” sequels. Remakes and series [rights] reverted to me about four years ago, but we don’t have foreign. So [to make a sequel] we have to find an investor who will go for a US-only distribution [deal]. In theory, that would be a good deal, because the US is by far the biggest market for the ‘Repo Man” phenomenon.

So do the terms of the original contract mean you could make a “Repo Man” sequel but you couldn’t show it outside of the United States?

We [could, but we] would have to sell it to Universal [first], because they own the foreign rights to a “Repo Man” sequel.

In theory, could Universal do a “Repo Man” sequel with some other director and only show it internationally, not within the United States?

Ironically, because of my contract, the only person who can direct a “Repo Man” sequel is me, so they’d [still] have to buy the foreign rights!

It all sounds very complicated!

It is complicated, isn’t it? But we are pursuing some interesting possibilities of finding some way that we can fund it, just from the US distribution [rights]. But the thing does not exist yet, except as a screenplay.

How many people need to see a movie for you to feel as if you succeeded overall, in whatever sense? Is there any number of viewers under which you would conclude, “Oh, well, that didn’t work out”?

No. Just making it is success enough. I mean, you can’t control how many people see it. How many people have seen ‘Repo Man’? How many people have seen ‘Tombstone Rashomon”? Pretty much everybody has seen “Repo Man,” yeah? Comparatively few people have seen “Tombstone Rashomon.” But I like them both equally, so that doesn’t make any difference. If you’re a film artist, if you’re actually a creative, artistic, independent filmmaker, you make films for yourself, and the pleasure is in the making of them, and in the collaborative process. And then, in the distribution, well— whatever happens happens.

That sounds like a healthy attitude.

It’s the only attitude you can take at the end, because you can’t really control distribution. And if you worry about how many people saw it, you’re not going to have any fun. You’re going to be filled with regret, and you’re going to value things that maybe aren’t so valuable.

But you know, the theater experience hasn’t gone away. There are still art cinemas, you know. There are still repertory theaters. It all still exists. People like to go to the cinema and they like to see things that aren’t just Marvel Comics movies. There is definitely hope.